The Day After

In his art Steve Creson never makes a mistake. His poetry, films, photographs, paintings, collages, and designs are all authentic expressions of his personality. It sounds simple, but all these genres tempt the artist to impersonate an idealized self, a self made in some sense to fit the genre. But Creson’s work is all of a piece, and perhaps because he has always worked with his hands for a living, he has never given in to the temptation to idealize himself or his world–or if he has, the results have never seen the light of day. Not to say he doesn’t have doubts. But doubts lead to introspection, and Steve certainly knows himself as an artist. This self-awareness makes his authenticity sure-footed.

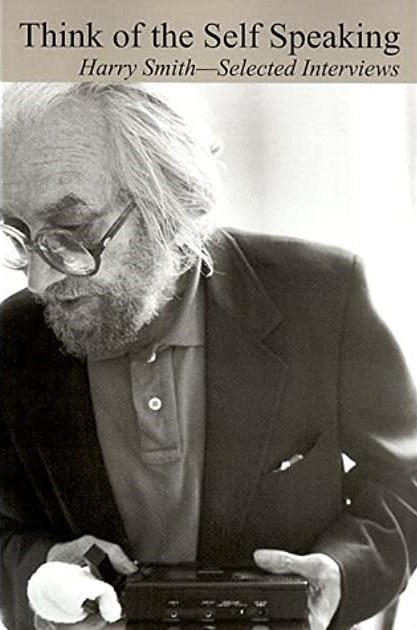

I first met Steve at the Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado, in 1988. Anne Waldman, director of the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics, had assigned us to share the duties as Allen Ginsberg’s assistant during the six-week summer session, so we had to keep in constant touch to coordinate our schedule. Neither of us had any idea such a temporary collaboration would lead to a friendship lasting more than thirty years. But the shared experience of attending classes, participating in performances, and hanging out with Ginsberg, William Burroughs, Gregory Corso, Harry Smith, and many other lesser-known artists associated with the Beat Movement–not to mention our fellow students, especially Andy Hoffmann and Darrin Daniel–created a rich foundation for our long relationship.

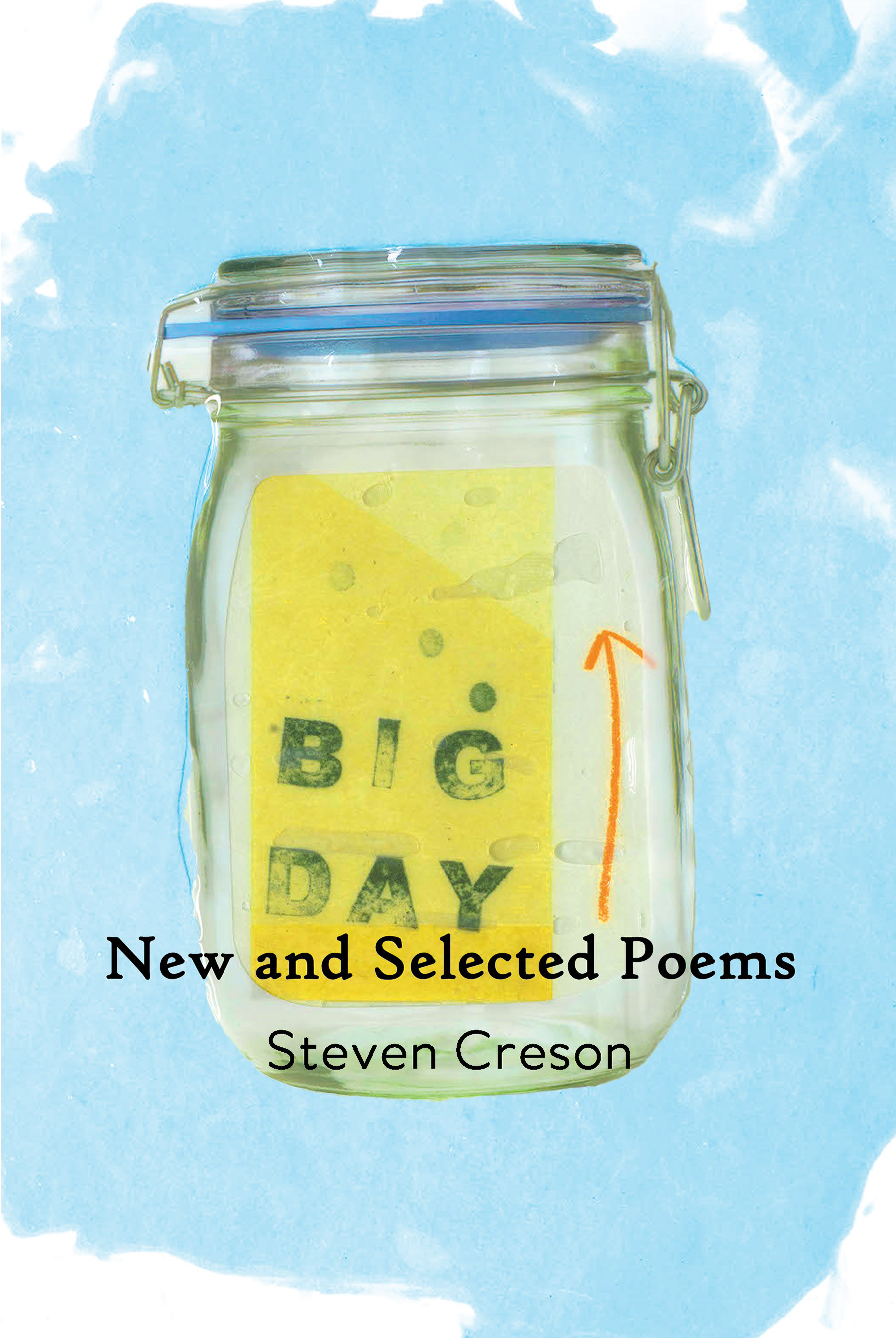

The next year I was in Ireland, while Steve went back to Berlin, just before the Wall fell. To my everlasting regret, I declined his invitation to come to Germany to see “something interesting that was happening.” But our paths crossed many times in many different places–some of them mentioned in these poems–in the decades that followed, and we always shared our writing, both published and unpublished. We share many of the same poetic interests and influences–including most of the ones mentioned in Big Day–so I think I could tell if he was imitating or even borrowing. Two more reasons I am so confident that he has never made an artistic error.

Like the poem “N (d),” Big Day begins near the present and ends with poems from early 1988, when Steve was living in Norfolk, Virginia. As the narrator says in section IV of “Distention,” “Today is a film in reverse.” Creson’s lifelong project is to imagine how his past determines the quality of the unfolding present. The attentive reader, then, will not be surprised to find so many references to dates, days, and even specific hours and minutes. The poet tries to pinpoint experiences that have some bearing on what he is living as he writes each poem. The result is a kind of bilocation, a feeling conveyed to the reader of being in two places at the same time.

The complement to time in these poems is image, like the series of still photos that make up every film. Theoretically, if time has material existence, we should be able to examine the instants of our lives as a film editor examines each frame, perhaps even cut and reorder them. But only theoretically, of course, at present. The problem is that the images keep accumulating as the past consumes the present–the camera only stops at death–and this problem infuses Big Day with creative tension, concisely expressed in section 8 of “Evaporation Blues”:

Unable to reconcile

the past and present, coming

From there and it is,

What went there is change

From where it was born is further

and further removed.

Despite the intense focus of Creson’s poetic imagination, the exact relation between the past and the present remains yet to be seen, to be written. Perhaps that’s why he often takes refuge in dreams (including a long book not included here called American Dreamer): no matter what their content, dreams are always all present.

I have a particular fondness for the “Now Poems,” which I had the honor to publish as a chapbook under the imprint of The Church of the Head Press (1996; copies still available from both author and publisher!). Their fragmented diction gives them a sense of immediacy, which, like a dream, lends them a sense of immediacy, as though in this series of poems, Steve had momentarily found an equilibrium between the pressure of the past and the fleeting nature of the present.

Fast-forward thirty-five years. Husband of a performance artist, father of a budding pop singer, easing into retirement from his successful construction business, Steve is still exploring new media, new projects, in his studio in Salt Lake City, still giving readings and showing–during the pandemic streaming–his films, mounting exhibitions of his visual art. The book you hold in your hands is his Big Day, the culmination of a lifetime of writing, but it’s not his final word.

At a memorial service for his father in his hometown of Auburn, Washington, Steve told a moving story about taking his dad to Montana late in life to visit places he had lived and worked. (Compare this episode with the moving poems about the death of Steve’s mother.) He was hoping the trip would cause his dad to open up about his past, but after a few days of driving mostly in silence, his dad asked to turn around and head back home. This episode strikes me as revealing about both men, father and son. Steve himself is somewhat laconic, as the terseness of these poems–especially the earlier ones–may suggest, but the urge to write, the years of practice, the previous books, his ‘zine Anatomy Raw, the public and private readings also represent his overcoming of his father’s reticence to tell his story, to open up, to represent imaginatively the presence of the past.

Big Day is guaranteed to be authentic, to teach the reader something important about the value of appreciating the tension between the present and the past, and to stand as the grand example of Steve Creson’s unfailing aesthetic sense.

-Jim Jones